*Meditation is an always-available gift of replenishment that we can give to ourselves anytime during our harried work schedule.

Researchers

are exploring the benefits of meditation on everything from heart

disease to obesity. Sumathi Reddy and Dr. Aditi Nerurkar join Lunch

Break.

Researchers

are exploring the benefits of meditation on everything from heart

disease to obesity. Sumathi Reddy and Dr. Aditi Nerurkar join Lunch

Break.

Doctor's Orders: 20 Minutes Of Meditation Twice a Day

At Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, doctor's orders can include an unlikely prescription: meditation.

"I

recommend five minutes, twice a day, and then gradually increase," said

Aditi Nerurkar, a primary-care doctor and assistant medical director of

the Cheng & Tsui Center for Integrative Care, which offers

alternative medical treatment at the Harvard Medical School-affiliated

hospital. "It's basically the same way I prescribe medicine. I don't

start you on a high dose right away." She

recommends that patients eventually work up to about 20 minutes of

meditating, twice a day, for conditions including insomnia and irritable bowel syndrome.

Integrative medicine programs including meditation are increasingly showing up at hospitals and clinics across the country. Recent research has found that meditation can lower blood pressure and help patients with chronic illness cope with pain and depression.

In a study published last year, meditation sharply reduced the risk of heart attack or stroke among a group of African-Americans with heart disease.

At Beth Israel Deaconess, meditation and other mind-body therapies are slowly being worked into the primary-care setting. The program began offering some services over the past six months and hopes eventually to have group meditation classes, said Dr. Nerurkar.

Health

experts say meditation shouldn't be used to replace traditional medical

therapies, but rather to complement them. While it is clear that "when

you breathe in a very slow, conscious way it temporarily lowers your

blood pressure," such techniques shouldn't be used to substitute for

medications to manage high blood pressure and other serious conditions,

said Josephine Briggs, director of the National Center for Complementary

and Alternative Medicine, part of the National Institutes of Health. In

general, she said, meditation can be useful for symptom management, not to cure or treat disease.

Dr.

Briggs said the agency is funding a number of studies looking at

meditation and breathing techniques and their effect on numerous

conditions, including hot flashes that occur during menopause. If

meditation is found to be beneficial, it could help women avoid using hormone treatments, which can have detrimental side effects, she said.

The most common type of meditation recommended by doctors and used in hospital programs is called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, which was devised at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Dr.

Nerurkar said she doesn't send patients to a class for training.

Instead, she and other physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess will

demonstrate the technique in the office. "Really it's just sitting in a quiet posture that's comfortable, closing your eyes and watching your breath," she said.

Murali Doraiswamy, a professor of psychiatry at Duke University Medical

Center in Durham, N.C., says it isn't clearly understood how meditation

works on the body.

Some

forms of meditation have been found to activate the parasympathetic

nervous system, which stimulates the body's relaxation response,

improves blood supply, slows down heart rate and breathing and increases

digestive activity, he said. It also slows down the release of stress

hormones, such as cortisol.

Dr. Doraiswamy says he recommends meditation

for people with depression, panic or anxiety disorders, ongoing stress,

or for general health maintenance of brain alertness and cardiovascular

health.

Thousands of studies have been

published that look at meditation, Dr. Doraiswamy said. Of these, about

500 have been clinical trials testing meditation for various ailments,

but only about 40 trials have been long-term studies.

It

isn't known whether there is an optimal amount of time for meditating

that is most effective. And, it hasn't been conclusively shown that the

practice causes people to live longer or prevents them from getting

certain chronic diseases.

Some short-term studies have found meditation can improve cognitive abilities such as attention and memory, said Dr. Doraiswamy.

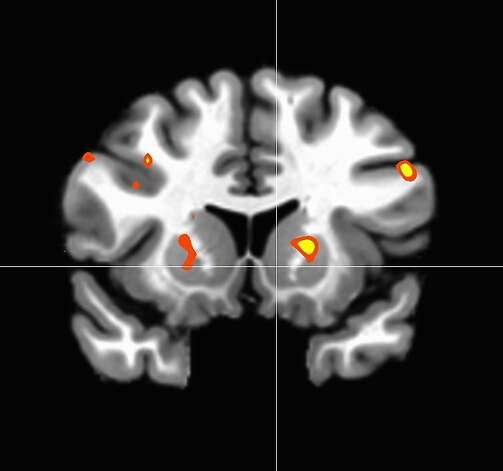

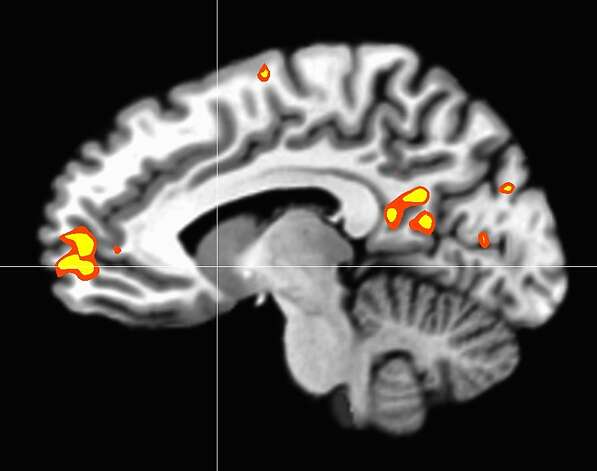

Using

imaging, scientists have shown that meditation can improve the

functional performance of specific circuits in the brain and may

reduce age-related shrinkage of several brain centers, particularly

those that may be vulnerable in disorders such as Alzheimer's disease.

Recent

research found that meditation can result in molecular changes

affecting the length of telomeres, a protective covering at the end of

chromosomes that gets shorter as people age.

The

study involved 40 family caregivers of dementia patients. Half of the

participants meditated briefly on a daily basis and the other half

listened to relaxing music for 12 minutes a day.

The eight-week study found that people

who meditated showed a 43% improvement in telomerase activity, an

enzyme that regulates telomere length, compared with a 3.7% gain in the

group listening to music.

The

participants meditating also showed improved mental and cognitive

functioning and lower levels of depression compared with the control

group. The pilot study was published in January in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Government-funded research also is exploring meditation's effect on dieting and depression.

Write to Sumathi Reddy at

sumathi.reddy@wsj.com

A

version of this article appeared April 16, 2013, on page D1 in the U.S.

edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Doctor's Orders:

20 Minutes Of Meditation Twice a Day.

More About the Mind and Body

Rewiring the Brain to Ease Pain 11/15/2011

Anxiety Can Bring Out the Best 6/18/2012

Source:

/article/SB10001424127887324345804578424863782143682.html?mod=WSJ_hpp_sections_lifestyle